This article was originally published in RHYTHMS magazine (Sounds of the City) September-October 2024 (Issue #325)

RICHARD CLAPTON – HELLO TIGER!

With the reissue of three of his classic albums and a run of dates throughout August – including his 15th annual concert at the State Theatre – singer-songwriter Richard Clapton has been busier than ever.

By Ian McFarlane

Album cover photo by Violette Hamilton. Art work by Geoff Kleem

The life of a touring musician can be, by turns, interminably gruelling and terribly hectic. With the shaggy haired, perma-sunglasses wearing Richard Clapton now such an established artist and public figure, having lived the touring life for 50 years, he knows the ropes. There’s lots of down time and waiting around, in the lead up to the show. Then the excitement of presenting a two-hour concert, in front of committed audiences, makes it all worthwhile. Playing live remains a perfect way for an artist to get their music across to the fans, that mix of buoyancy and intimacy that can make the event so enthralling.

“It seems the older I get the busier I get,” he tells me when we connect. “But it’s just the modern age. The modern age is like that parable of the tiger running around the palm tree chasing its tail and it ends up turning into butter. That’s how the human race is now.”

As well as the State Theatre, his tour itinerary took in shows in Birdsville (Big Rock Bash), Broken Hill (Mindi Mindi Bash) and Gympie (Gympie Music Muster). Clapton has always surrounded himself with high quality musicians. There are too many to mention here, albeit pertinent to say that his current band includes regular members Danny Spencer on guitar and Michael Hegerty – who’s been with him, on and off, for 45 years – on bass.

Clapton spent much of his formative, pre-fame life travelling around Europe. He’d based himself at various times in London and Berlin. He drew on much of those experiences when it came to his song writing craft. On his return in 1972 he set about getting those songs heard. For most of his professional life, he’s been known as Ralph. Does he ever get tired of that name?

“No, I never get tired of it. I call myself Ralph now. It’s just a nickname. It’s ingrained in everyone, a bit contagious. Some people thought it was offensive. It’s a dumb, simple story. When I got back from Europe... I’d been in London for four and a half years, living in Kensington, and it took me a while to lose the southwest London accent. I was talking like, ‘know wot I mean, guv’. I had long hair. I was doing a gig, Chuggy (promoter Michael Chugg) was my manager. The roadies were packing up afterwards and everyone’s getting drunk. One roadie kept looking at me and saying ‘Ralph’. I kept turning around going, ‘Who the fuck are you talking to? Who the fuck is Ralph?’. He says, ‘You, you’re Ralph, the hairy English sheepdog, you know from the cartoon’. That stuck. Chuggy started calling me Ralph, and it’s gone on from there.”

The other great news for Clapton fans is that Warner Music Australia has reissued three of the singer’s classic, long out-of-print albums. With brand, spanking new LP and CD editions of Prussian Blue, Goodbye Tiger and The Great Escape on the market, we are now reminded of just how important these recordings are. The LPs present the same music programme as originally conceived, with the CDs adding rare bonus material.

Musically Prussian Blue (November 1973) might have been tentative is some ways, a typical debut, but it put Clapton’s creative endeavours on full display. There were country rock sounds, melancholy folk rock jangle and moments of tough Aussie bar room rock. His song writing was already fully formed, with the likes of ‘Last Train to Marseilles’, ‘I Wanna be a Survivor’, ‘All the Prodigal Children’ and the reflective title track providing the basis for all he’s done since.

Goodbye Tiger (August 1977) is a genuine classic of Australian ‘70s rock. A quote of mine has appeared in the press release, and it still hits the mark (if I don’t say so myself): “Goodbye Tiger remains Clapton’s most celebrated work, an album full of rich, melodic and accessible rock with a distinctly Australian flavour. It established his reputation as one of our most important songwriters.” The album reached #5 on the charts.

Intriguingly, part of the inspiration for the record had been seeing noted American gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson on his 1976 Australian tour, immediately after which Clapton flew off to Europe to write the songs. He’d finally taken advantage of the travel grant he’d received from the Australian Arts counsel. Even though the songs had been written overseas, they were essentially about his homeland (more on which below). And it’s the quality of the songs that still stands out, such as the hit single ‘Deep Water’, ‘Down in the Lucky Country’, ‘Wintertime in Amsterdam’ and the elegant title track which caught the mood of the day.

Having initially signed a record deal with Festival Records, for release on the Infinity imprint, Clapton signed a new deal with WEA which resulted in another strong album, The Great Escape (February 1982). Produced by Mark Opitz (Angels, Cold Chisel, Hitmen) it boasted a solid rock base. It reached #7 and spawned three singles, the hard rocking ‘I am an Island’, the ballad ‘Spellbound’ and the perennial ‘The Best Years of Our Lives’. I call the last-mentioned track “perennial” because, not only did he think highly enough of it to have called his 1989 live album after the track but also, he bestowed it upon his 2014 autobiography. Furthermore, it’s always been a showstopper at his concerts.

The arrival of the reissues has been most welcome and timely. Then again, the process of getting the reissue programme underway and the finished product on the market must have been incredibly drawn out?

“You betcha it was,” the singer states emphatically. “I don’t want to say too much, but it’s been a long haul. Terry Blamey started managing me several years ago, he was responsible for getting me to record my hippie anthems album, Music is Love. Terry was trying to reach out to Warners for quite some time because he’s a big fan, that’s why he’s hanging out with me, and he’s got his favourite albums. We were getting nowhere; it’s been touch and go with Warners. Then I was having coffee with John O’Donnell, he’s been a long-time supporter, and he jumped on board. He’s got a relationship with Dan Rosen at Warner, so it was a fast process from then on in. Don Bartley has remastered them. He’s worked on so many of my albums, he’s got the masters to nearly every album I’ve done. Glory Road was mixed in America, mastered in America. Hearts on the Nightline was recorded in America, so we don’t have those masters.”

Some Clapton Classics and Deep Cuts

In an attempt to explore the Richard Clapton experience, let’s go on a deep dive into his catalogue. With sixteen studio albums and three live ones under his belt, there are a multitude of songs on which to draw, but I’ve selected ten songs that I see as signposts along the way.

‘I Wanna be a Survivor’ – “I see my ship, she’s down there in the harbour / I hope she waits for me to board her / ‘Cos I wanna be a survivor / and I’m gonna be a survivor / And I won’t come back / Even if I live to be a thousand years”

This strident statement depicts a young man living in a city ghetto who is intent on escaping the strife and pain of his urban existence. It’s emblematic of the album. Other singers of the day quickly picked up on Clapton’s message, including Jeff St. John who made it a feature of his concerts. What memories does Richard have of recording Prussian Blue?

“I don’t remember anything negative about Prussian Blue. The producer, Richard Batchens, was recruiting some of the best players around Sydney at the time. The La De Das are on ‘I Wanna be a Survivor’, which sounds like the La De Das, pretty much. We had Don Reid on sax, a lot of jazzers. Then on Mainstreet Jive we had Crossfire, Batchens got them in as session musicians. Years later I was amazed at how famous John Capek had become in the States. He played on ‘Last Train to Marseilles’. We had Mike Perjanik on piano.

“Most of those songs were written in Europe. I’d been living in a commune in Berlin. The main guy there was Volker, and he took me in when I had no money. He was about eight years older; he was my mentor. There was Georgie, a hippie farm boy from Bavaria, he married one of the girls who had come from a very rich family. There’d been a big altercation in the commune and some of them left. They got me to stay in this huge mansion, I was there by myself for a while. I was writing about my experiences in Germany. ‘Southern Germany’ was written literally. ‘Burning Ships’ was a heavy song about a girl who overdosed in a nightclub when I was with her. ‘All the Prodigal Children’ is more London, a slice of real life.

“I got back to Australia, homeless again, crashed out at this guy’s place in Redfern. Hence ‘Strange Days in Chippendale’, at that point in time it was very gritty. ‘I Wanna be a Survivor’ I wrote after I’d done the deal with Festival and I’d received a pittance, enough to pay rent on a little shithole in Kings Cross. I did have a great view right over the harbour. Life was very tough for me at the time. I was hoping for the best, and the deal with Festival with Prussian Blue was gonna lead on to bigger and better things. Therefore ‘I Wanna be a Survivor’ makes sense. It was a statement of intent.”

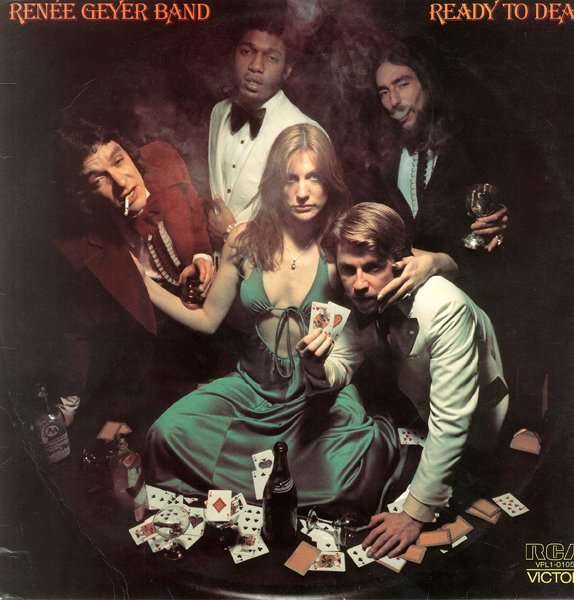

Album cover photo by Graeme Webber Returb Studios

‘Girls on the Avenue’ – “Girls on the avenue, know how to get you in / Casting out sighs like tricks from a hat / All the miss Lonely Hearts, oh they look awful hard / Then sometimes they seem as fragile as glass”

This was his first major chart hit, a national #2 in 1975. The song came adorned with a gorgeous guitar refrain played by country picker Red McKelvie, and it remains one of his most iconic songs. Festival staff had shown little interest in the song initially, relegating it to the B-side of ‘Travelling Down the Castlereagh’. Strong radio support forced Festival’s hand; it was reissued as an A-side and picked up by the fans en masse. Oddly, it has been suggested that it was written about ogling ladies of the night as purely sex objects, but that’s not so...

“I was hanging out with Colin Vercoe, head of publishing at Festival. We lived in Rose Bay and the next street along there were three pretty girls that lived in this house, it was written about them. Festival had wanted to drop me. Prussian Blue got good reviews – there was a great one in Rolling Stone – and I thought ‘that’ll put me on the map’. All Festival cared about was money, they didn’t care about an artist showing promise. Getting good reviews might have been well and good, but it was all about getting good sales.

“Colin was responsible for getting me to write ‘Girls on the Avenue’. He kept imploring me, ‘make one compromise, man! It will enable you to make another album. Go from there and when you’ve established yourself artistically, you can do whatever you like’. Festival would have their A&R committee meetings every Tuesday, where they’d decide what singles to release. Colin invested so much of himself personally in that record and they kept rejecting it. Colin was getting increasingly agitated, and it dragged on for weeks.

“Then Colin had been having secret lunches with Marius Webb and Ron Moss, who founded Double J. On the last occasion he had lunch with them he got really drunk, took the job as the first music programmer at Double J and went back to the selection committee at Festival. For the final time they said, ‘No, we still don’t get it, it’ll just be a B-side’. Colin took a swing at one of the executives, ‘Well, fuck you’... ‘No, fuck you’. He goes ‘You know what, I’m going to be the first music programmer at Double J’, and walked out. He played ‘Girls on the Avenue’ every hour, on the hour, and because of that it got picked up everywhere and became a huge hit.”

‘Blue Bay Blues’ – “Janie, see how the sky looks today / I bet they’re having fun up in Byron Bay / All our friends – ah, I’m feeling just a little bit blue / I can tell it’s been getting to you too / Tryin’ to make sense / ... and I got those blue bay blues”

Another splendid track from the Girls on the Avenue album, this introspective, reflective folk ballad displays plenty of charm.

“That came out unscathed. Richard Batchens was happy with that very simple arrangement, just Mike McClellan and me playing acoustic guitars with the band I had at the time. There were some unpleasant experiences recording that album, however.

“Richard was called the house producer, which means he thought he had the authority vested in him to produce in any way he saw fit. But he put in a string quartet, two violins, two cellos and it was crappy. We had a big falling out and I stormed out of the studio. I went home, I was living in a one room bedsit in Bondi Beach. ‘Girls on the Avenue’ was powering up the charts at #2, started as a B-side by the way, and I thought, ‘Fuck ‘em, they must have spent 100 grand on it by now, I won’t call them, I’ll make them call me’. It was over a week and my phone hadn’t rung! (laughs). How could record companies do this? I’d just had an argument with the producer, and I assumed they’d thrown the album in the trash can.

“But no, they hadn’t done that. After seven days I went sneaking back to Festival, at about 7.30 at night. I snuck up the back stairs, which is where the studio was and I could hear Richard working on ‘Rose Wine Cafe’ without me, doing whatever he wanted with it. I snuck around in the darkened hallways, and I bumped into the managing director. He said, ‘Richard, what’s going on? We haven’t seen you for days; what’s up?’. And I said, ‘I really don’t like what Richard’s doing with my songs’. And Jim goes, ‘You mean our songs’. ‘What are you talking about?’, I said. ‘They’re our songs, so Richard can do whatever he wants’. He said, ‘Come into my office’. He got out the contract and said, ‘Have you read this?’. I lied. This was my first contract, I was too young and naive, I was so excited to get a record deal. I just signed off. He said, ‘You’d better read this clause here; they’re not your songs anymore, you assigned your songs to us and they are now property of Festival Records’.

“I obviously learned the hard way but once you sign a contract that’s not your property anymore. In other words, I wrote ‘Blue Bay Blues’ but it doesn’t belong to me. I wrote ‘Girls on the Avenue’ but it doesn’t belong to me. If Festival wanted to do anything, do a reggae version of ‘Blue Bay Blues’, they can do anything they like without my permission.

“Then when Rod Muir first became my mentor – he was fabulously wealthy, a multi-millionaire – he approached Festival and said, ‘I’ll give you one million dollars for Richard’s whole catalogue and they said, ‘No, forget it’. Rod said two million, stupid money and because it was owned by Rupert Murdoch, his policy is he retains copyright until 50 years after the artist’s death. It got a bit better because Michael Gudinski ended up buying my whole Festival catalogue and the publishing and moved it over to Mushroom.”

‘Factory Life’ – “And they’re so tired of the factory life / Try to escape it on Saturday night / Pick yourself up and open your eyes / Get yourself out of the factory life”

Mainstreet Jive (1976) yielded the uptempo single ‘Suit Yourself’ and the soulful ‘Need a Visionary, while the hidden gem was this ode to the search for a better life. By this stage, Clapton had added Canadian master guitarist Kirk Lorange to his band; he played slide, lead and acoustic on seven of the album’s tracks, while it’s Mario Millo who takes the lead solo on ‘Factory Life’. Did Richard remember writing that one?

“Yeah, I do but I’d approach it from a different angle. Insofar as all the students in that commune in Berlin were left wing, very anti-right and they had Nazi parents who they all hated. After I’d been in the commune for two or three months, I felt guilty ‘cos I had no money. Volker would give me 10 deutschmarks to buy cigarettes and a bit of food every day. It was a proper commune, I’d go to the market to buy vegetables to make the casserole, clean up the apartment, all that sort of stuff.

“One of the girls in the commune had contacts at the British Embassy and she got me a job as a gardener. That night we were having dinner and I told Volker, in half broken German and English – he’d taught me some German – I said, ‘I’ve got a job, all I have to do is mow the lawns’. He goes, ‘What!? You said you were a songwriter’. I said, ‘Yeah, but I gotta pay my way’. He was very guttural German when he got mad, he yelled, ‘If you want to be a gardener, there’s the door, see you! Do you want to be a songwriter?’. I said, ‘Yes’ (laughs). Volker was a lecturer at the university, and he had access to these old Revox tape recorders and next day he came in with this big tape recorder and a Neumann mic. He set me up in one of the spare rooms, he said, ‘You sit there and write songs’.

“Now getting back to ‘Factory Life’... I really looked up to Volker and, because he was very political, he had a thing about Marshall McLuhan (Ed note: Canadian communication theorist who coined the phrase “the medium is the message”). Volker was educating me to write songs that were commercial and successful. He didn’t want me to write protest songs that hardly anybody would hear, he wanted me to write songs that would be heard on the radio. After Prussian Blue I kept going back to Berlin and Volker kept urging me to get the message across subliminally in a candy coating. The best example of that is ‘High Society’, I think, my most successful sugar-coated song.”

‘Capricorn Dancer’ – “Gypsies ride from wonderland / I took my horse down to the sand / Underneath a thousand miles of sky”

This enchanting song is one of his most successful folk rock ballads, a whimsical ode to an idyllic and carefree existence, a way to ease his worried mind. It was one of six Clapton songs included on the soundtrack to Steve Ottens’ surfing film, Highway One (1976).

“That’s an odd one out. That came about because I’ve always had a penchant for wanting to write a film score ‘cos I’m a real movie buff and always have been. That came out of the blue. I’d received the Arts Council grant to go overseas, and I’d already booked my travel plans and, at the last minute, David Elfick, who produced Highway One, approached me to write the songs. It was a mad panic, I wanted to do the whole album but I didn’t want to miss my flight back to Europe. ‘Capricorn Dancer’ was written lightning fast and recorded lightning fast. All those songs were done in one or two takes. I had about two days to get them done.

“I wrote ‘Capricorn Dancer’ sitting in front of the film rushes. They set up a film projector in the studio, projected the images on the wall. I would sit, writing then and there. You’ve seen the film clip? And they synced the song perfectly to the visuals.”

Courtesy of Richard Clapton

‘Deep Water’ – “They closed down the doors of the Trocadero / And I came back looking like a ghost / The posters are scattered all over the stairs / Nobody read them so nobody cares”.

The Goodbye Tiger album represents a masterclass in song writing and this is probably the highlight. It was unlike anything else heard on commercial radio at that time, a deep-seated rumination on times already fading, evocative, moody and elegiac all at once. The album’s layered production sound is front and centre but it’s not overproduced, so it retains a gritty toughness shot through with bitter emotions, faded glory and deep regret.

“That song is very melancholic. How I wrote the songs on Goodbye Tiger... I went up to Norre Nebel in Denmark, with friends. German students would go up there for winter break. We’re sitting up there, it’s 30 degrees below zero, it’s so cold even the beach is frozen. I was living in this lovely house, Air B&B nowadays you’d call it. The Germans would be having their intellectual raves and rants. I had a little attic room, and it always piqued my curiosity, it was freezing and I wanted to write a song about Bondi Beach (laughs). I don’t know, there’s obviously some mental process there.

“I say in interviews now that I wrote those songs, the Australian songs which were written from Denmark, because of homesickness. I was finally confessing up to the fact, yes, I did get homesick. But it was a marvellous experience writing those songs.

‘I am an Island’ – “Little darling this is the end / I needed you like oxygen / ‘I am an island’ some sucker scrawled / I am an island on a city wall”

This was the powerful lead-off single lifted from his seventh album, The Great Escape, and it was another Top 20 hit. The lead guitar work is credited to Harvey James (from Sherbet) but it subsequently came to light that another foremost guitarist was the main man.

“In the early 1980s, Ian Moss and I used to hang out a lot. Mossy loved ‘I am an Island’, as soon as I wrote it and he wanted to play guitar on it. Then Cold Chisel went on tour to America and Mossy would call up out of the blue, at all hours of the night and go, ‘What are you recording?’. I’d say, ‘The Best Years of Our Lives’, and I’ve got Mick ‘The Reverend’ O’Conner on Hammond organ and it sounds fucking awesome!’. He’d say, ‘Yeah, I want to be on that’. He called me up from LAX and said, ‘What are you doing now?’, ‘I am an Island’... ‘I wanna play on that!’.

“Mossy jumps on the plane, got back to Sydney, came straight over to Billy Fields’ studio Paradise, he and Mark Opitz ordered 11 Marshall amps. They pretty much went bang bang bang, his guitar solo was down. And Jimmy Barnes and I were best friends also and he ended up singing on ‘I am an Island’. Don Walker came in and played piano on ‘I Fought the Law’. Then their manager, Rod Willis, found out and went ballistic! He called Paul Turner, head of WEA, and demanded, ‘You fuckin’ take my band off Richard’s album!’.

“Chisel were on WEA at the same time as I was, so Paul held the upper hand and he said, ‘Tough titties, no I’m not taking them off the album, it sounds fantastic’. They had a huge fight and Paul won, in my opinion. The compromise was taking the Chisel guys’ names off the cover. The Rolling Stone article came out and the writer was raving about this great album and how it had now established Harvey James as Australia’s greatest ever guitarist. He played on the record too and then toured in my band but it was really Mossy playing the guitar solos. I was reading the Rolling Stone review at Sydney airport and Mossy comes over and goes, ‘What the fuck is this!? Where’s my credit on the album?’. I just had to say, ‘Speak to your manager’.

“Even though it stayed like that, Jimmy would never shut up about it. He’d do an interview and say, ‘That’s me, I’m singing on Richard’s album’. Fast forward 40 years and John O’Donnell is the co-manager of Cold Chisel, and John was producing Diesel’s new TV show on SBS and he got me over to Botany to work on Diesel’s TV show all day. He lives near me; he drove me home and it took two hours to get to Neutral Bay from Botany. We’re sitting in the car chewing the fat and John kept going on about The Great Escape. He was so glad that we’d chosen it as one of the three albums we’d reissue. I told him the whole story. He goes, ‘You gotta be kidding me! We’re gonna get this fixed’. So, we made sure that Mossy’s name was on every song (laughs), just to make it up to him.”

(It’s pertinent to acknowledge that the late Harvey James was indeed a phenomenal player, it’s just that Ian Moss was due his credit.)

‘Solidarity’ – “Hey kid! Don’t you lean on me / I wanna talk to you ‘bout Solidarity / Hey Ma! I keep falling on my knees / And I need you now in Solidarity”

Once again produced by Mark Opitz, the Solidarity album (1984) was Clapton’s bold move into modern recording technology and keyboard programming. There’s also that ‘gated’ snare drum sound but the likes of ‘The Heart of It’ and ‘Cry Mercy Sister’ retained Clapton’s soulful tang. The anomalous, sequencer heavy title track might have been influenced by newer electronic bands such as Machinations, for example, and it’s the highlight.

“I really like that song, such a different style of song, particularly the keyboard sequencing. I got caught up in that early ‘80s technology, and I’ve been trying to get the message out to the kids that you can’t let this technology control you, you’ve gotta make sure you’re the master of this technology, not the other way round.

“So that album being 1984, that’s when that technology had taken off. Drum machines were popular, sequencers. Roland had made a bass sequencer. You’d put a pattern into it and press the button and it would arpeggio it all. That was the whole synth line in ‘Solidarity’. And once again, I don’t try to hide the fact it’s a very European song in its flavour. Even the lyrical attitude was different. All my songs don’t have to be about Australia. I had been in Europe for a long time. We’ve just started putting that back into the set. We’ve extended the intro, almost two minutes, and it’s a good way to start the night off.”

‘Everybody’s Making Money (But Me)’ – “I got holes in my pockets / You can feel my naked leg / Every time I reach for money makes me wish that I was dead / Now the politician’s telling me that it’s gonna set me free / Everybody’s making money except me”

Clapton recorded this rocking, mocking, bitter rant in the late ‘70s but it remained unreleased until included on The Definitive Anthology (1999).

“Believe it or not, one of my many frustrations – I have so many frustrations – I’ve come so close to international acclaim and I’ve had it snatched away by politics back here. This is another Festival Records story, because one of the biggest publishers in Nashville heard that song and just loved it but Festival had the publishing on it. It was only on that compilation, so (laughs) that song’s about managers in general. It’s the ballad of the muso. It’s the only time Andy Durant (Stars’ guitarist-songwriter) played on a record with me.”

‘Dancing with the Vampires’ – “And now the party’s over / Gonna clean up all this mess / Gotta pick up all the pieces / Wipe the stains off mama’s dress / That wasted Casanova / Gon’ and passed out on the floor / He’s been crying out like a baby / Couldn’t take it anymore”

Another tough rocker, tinged with stoic resignation, the single taken from the Harlequin Nights album (2012).

“I think I was calling that my divorce album. I had a big empty house. Danny Spencer used to come up to Sydney to play with Jimmy Barnes, also Jon Stevens, Friday and Saturday nights. Cos we’re all mates, Danny would say ‘I’m going to stay at Ralph’s place’. He’d do the gigs and then stay with me for three or four nights; I had plenty of room in the house. We worked on things so that was one of the highlights of my professional life because it was so liberating. There was no producer.

“I did have a sugar daddy, another multi-millionaire (laughs) without whom I’d probably be in a homeless shelter. Ross Jackson was just a massive fan. He owns Jackson’s Electronics. He got me to play at his 45th birthday and he wanted to invest in my career. I was telling him I had all these new songs. He said, ‘What about doing a new album and I’ll finance it’. I said, ‘In my experience it is very expensive to record in a professional studio, I don’t want to impose upon your finances’. I told him about Pro-Tools, the computer music program. I claimed I could make an album as good as anything I could do in a studio.

“Ross outlaid 35 grand for the Pro-Tools rig, all the PCI cards. I ended up with about 50 grands worth of equipment in my home studio. I could just spend days and days down there, working with top technology. It would have been like The Band recording at Big Pink. You’d just go downstairs and record. I remember when we recorded Rewind, Danny just stayed down in the studio for three and a half days straight. I’d say, ‘Danny, enough already’ and he’d say, ‘No man, I’m really starting to nail this’. So Harlequin Nights is very near and dear to me because of the subject matter.

Music is Love

Music is Love (1966-1970) has been Clapton’s most successful latter-day album (2022). In presenting 12 well-known Californian songs – such as ‘Get Together’, ‘Riders on the Storm’, ‘Summer in the City’, ‘Eight Miles High’, ‘Woodstock’ and ‘Cinnamon Girl’ – and treating them reverentially, while retaining the Clapton touch, his fans responded positively. He tells me that he and Terry Blamey had curated the project over a period of two years but that he didn’t warm to the idea initially. Once Blamey (previously Kylie’s manager) had convinced Michael Gudinski to finance the recording, he thought, “What have I got to lose?”.

“The song writing thing is becoming the bane of my existence; that’s a whole other interview to talk about. I hadn’t been writing songs for a couple of years at that stage. Over a couple of weeks, I let the idea percolate. Terry said, ‘Honestly, I’ve got a good vibe on this’, and I agreed. The whole thing just evolved organically. Gudinski put the money up but he and Warren Costello at Bloodlines didn’t interfere at all.

“I started out thinking about doing British songs. I’ve been a lifetime Stones and Kinks fan. I wanted to do ‘Waterloo Sunset’ and ‘Street Fighting Man’ but I thought I’d be spreading myself too thin. I wanted a centrifugal point to the whole thing, so we decided to keep the London anthems for a Volume 2. The only thing that stopped that has been Michael’s death. When the hippie album went to #1, he was over the moon. He knew I was interested in doing a British hippie album as well, but sadly he passed away so end of story.”

As we sign off, I ask him how he reflects on that idealistic young songwriter recording Prussian Blue 50+ years ago?

“Well, to be honest I’d rather not answer that. I’m not trying to be a Mickey Downer but I’m worried about the state of modern music. There is so much that’s really bad and it’s affected my desire to make music. It’s not just me; I think there are so many worthwhile musicians all around the world who are screaming at the human race, ‘Are you listening or not?’. Everything is getting out of control with the AI thing now. We’re all starting to get impudent because what’s the point? I’m not doing this for the money but being raped and pillaged as we are, it’s just soul destroying, literally.

“To turn this around, I’m 76 and that’s every reason to be cheerful. I’ve led the life. I saw the Rolling Stones in Hyde Park in 1969. I saw Syd Barrett play with Pink Floyd; it’s almost a perfect life and I feel sorry for almost everyone else that it’s over.

“I do love performing and I love my bands. My fans are incredible; I can’t believe I’m so blessed to have such dedicated fans. In terms of making more records, I don’t know, it’s hard to get a good vibe. But thank Christ I wrote those songs when I did, because now I’m just a performer. I’ll never get sick of performing; it’s what I do best.

“How do I see myself retrospectively? I am blessed to have had so much success but I’ve had bad luck too. As Van Morrison sang, ‘I’ve been used and abused, I’m so confused’ (‘Brand New Day’). I couldn’t be more grateful for the body of work I’ve created over 50 years, there is that. I’d still like to be writing songs but it’s very hard to find something tangible to get hold of. The inspiration I’ve had in the last 50 years, that’s just not around anymore. That’s why I’m screaming at everyone, ‘Can’t you see where this is going everyone?’. AI and androids and robotics, this is just madness now. I don’t think I’m answering your question properly but I am very grateful, thank you.”