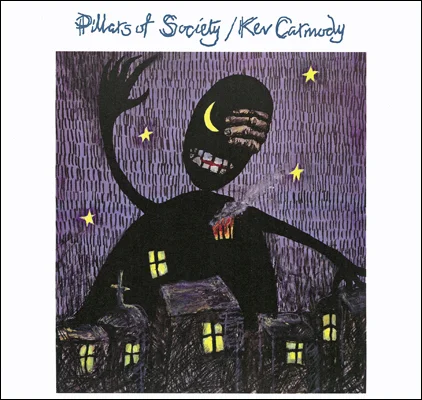

Kev Carmody - Pillars of Society

Kev Carmody’s debut album is celebrating its 30th anniversary

Originally published in Rhythms magazine Nov/Dec 2018 Issue #290

By Ian McFarlane © 2018

It’s remarkable to consider that singer/song writer Kev Carmody’s acclaimed debut album, Pillars of Society, is now 30 years old. Magnetic South Records have reissued it on LP for the first time in 28 years. If you’re lucky you might be able to score one of the limited edition coloured vinyl copies, half black, half red which when combined with the yellow centre of the record label replicates the Aboriginal flag.

Powerful songs such as ‘Pillars of Society’, ‘Black Deaths in Custody’, ‘Thou Shalt Not Steal’ and ‘Jack Deelin’ cut to the heart of the matter, highlighting the oppression and ignorance facing indigenous people. The songs elicit a deeply emotional response, conveying a sense of street-level reality by laying bare the truth of white Australia’s treatment of its land and first people. The original release, issued on the Rutabagas label in the Bi-Centennial year of 1988, was immediately hailed by Bruce Elder in Rolling Stone as “the best protest album ever made in Australia”. Yet was that the maker’s intention?

“Ah Ian, no way, no way...” is his empathic reply. “Don’t forget that in Queensland at the time we’d had the Bjelke-Petersen regime. I had a file as long as your arm at Special Branch with my activities, protesting the Commonwealth Games and the indigenous stuff. That brought a whole lot of people together, there was a whole movement up here, not only indigenous people. Eventually the Fitzgerald Inquiry got the police and the government held accountable for what they were doing. I used to turn up at the protest meetings with an old song like ‘Midnight Special’ that everybody knew and I’d just put Queensland words to it. ‘If you ever go to Queensland you better walk right/You better not fight the system/They’ll arrest you on sight/They’ll verbal you on down/Next thing you know my friend you’re Boggo Road Gaol bound/Let the Midnight Special da da da-dah’. That’s one verse I remember.”

In the late 1980s, after he’d completed a PhD in History at the University of Queensland, Carmody was considering his next move.

“I’d been writing songs since about 1967 and just kept them in a folder. It was coming up to the Bi-Centennial and the family said ‘you’ve got all these flaming songs, you should get some of them recorded’. I used to go into 4-ZZZ in Brisbane and do a live-to-air, we had a thing called The Koori Hour, so we’d record that and send it all around Australia. So there was no concept of ever going to a record company and being a celebrity. In ’88 I went to Sydney for the first time and recorded the album on an 8-track in Megathon Studios. They were still bolting the studio together actually. Later on the Oils recorded in there, it was in a big old warehouse. Of course, not having too much money we just made an acoustic album and there are some tracks on it like ‘Comrade Jesus Christ’ where there’s no music at all, I just got in front of the microphone and repeated it as a poem.”

As well as the potent messages in the lyrics (the content), it’s the sound of the album (the form) that grabs you immediately. The simple folksy and bluesy arrangements have an immediacy about them, relatively unadorned but very powerful, with Carmody’s rich voice to the fore. One can detect everything from the sounds of Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie to country blues and the Irish folk tradition in the sounds.

“Well, there’s a bit of everything in there,” Carmody confirms with a chuckle. “When I was growing up, back in the 1950s, we used to listen to those old Regal Zonophone gramophone records. We had Tex Morton, early Slim Dusty and the Australian mob. Then we heard Hank Williams and Patsy Cline. We heard blues music, Big Bill Broonzy, Leadbelly, Blind Willie McTell. This was before The Rolling Stones and The Beatles. We also heard an old aboriginal fella called Uncle Frank, he was a mouth harp player. He taught us the basis of the mouth harp on the droving camps because you couldn’t carry a guitar on the pack horses. In the ’60s we heard Jimmy Little, Lionel Rose, Auriel Andrews and Vic Simms. Oh yeah, Vic was the man! Johnny Cash went from the outside of the prison to the inside, Vic went from the inside of the prison out. He was genuine. Later on we had No Fixed Address and Yothu Yindi.”

The bluesy ‘Twisted Rail’ is populated by characters such as Fast Willie, Malcolm “with a razor and jack-knife up his leg”, Crooked Louis “who can’t lay straight in bed”, Blind Arnold, Sexy Sandra...

“Well, there are a few real people in there. There was a police commissioner named Lewis, he wound up getting sentenced to 14 years for corruption and forgery. That was basically just a blues guitar piece that I put words to. Fortunately, the lyrics came really easy to me. A song like ‘Thou Shalt Not Steal’, it came out so quick. I used to ride my push bike to the uni, across the Indooroopilly bridge. Sometimes coming home I’d sit and look at the beautiful sunset on Mt Coot-tha, and that whole song just came to me. With ‘Comrade Jesus Christ’, that was an esoteric, surreal linguistic poem about what Jesus meant to me. It was completely different from what the conservative, fundamentalist Christians were going on about.”

Pillars of Society did much to bring a whole raft of issues to light. For all the politicians’ talk since then, and the way bands such as Midnight Oil have managed to raise the bar, there’s clearly a lot more that needs to be achieved. We need to keep addressing the inequalities that affect indigenous people.

“Gee, we gotta keep at it,” is Carmody’s assessment. “If you look at a lot of lyrics these days, they can’t really help because it’s all about ‘me, me, me’. It’s all about the individual, whereas our stuff was always about community, ‘us and them over there’, the Pillars of Society, you know, buggering us around. We were always talking about us together. With so much communication these days we need to keep that political discussion going.”

In his 70s now, Carmody has essentially retired from creating music. Over the years he has worked with some incredible people... Paul Kelly, Steve Kilbey, Steve Connelly. He co-wrote ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’ with Kelly, as close to an alternative National Anthem as we’ve got. Alongside Pillars of Society, the Cannot Buy My Soul tribute CD-concert-DVD remains an important statement in his career. People have come to accept his songs as traditional folk songs, just part of our community now.

“Paul Kelly put that whole Cannot Buy My Soul project together. It was so great to be involved with that, just to have people like Steve Kilbey, Archie Roach and Bernard Fanning interpret the songs, put their own stamp on things. It felt like they weren’t my songs anymore, they become our songs, everybody’s songs. It’s always been the concept I’ve had with music, not the concept of celebrity and the ego up onstage.”

Pillars of Society track listing

SIDE 1

1. Pillars of Society

2. Jack Deeling

3. Flagstone Angels

4. Attack Attack

5. Thou Shalt Not Steal

SIDE 2

1. Black Deaths in Custody

2. Black Bess

3. Comrade Jesus Christ

4. Twisted Rail

5. White Bourgeois Woman

(All songs written by Kev Carmody)

Pillars of Society is now available on LP from Magnetic South Records.

Here’s an extra piece from my interview with Kev Carmody which I was unable to fit into the original article. He describes how he came to write the poem ‘Comrade Jesus Christ’.

“I don't want to mention what newspaper it was but they had a section in this provincial newspaper that you could send stuff in. So I sent in a poem that was very esoteric about what Jesus meant to me. It was an extremely conservative area during the Bjelke-Petersen era, a lot of fundamentalist Christians around but they printed this poem in the newspaper. I thought ‘holy mackerel, this conservative newspaper, I think they missed the point of this poem’. I thought I'll do a similar poem but do it in kindergarten language, people might get the point. I did this one called ‘Comrade Jesus Christ’ and I sent it in and they rejected it. They couldn't understand it, see (laughs), but they liked the one a few months before saying the same thing about Jesus, just looking at it in a different way. I thought Jesus was a man of love and compassion, that’s what I’m saying in the poem, not talking about the money making fundamentalist concept. Even the community radio stations had a fundamentalist Christian audience, they didn't want to hear about that.”